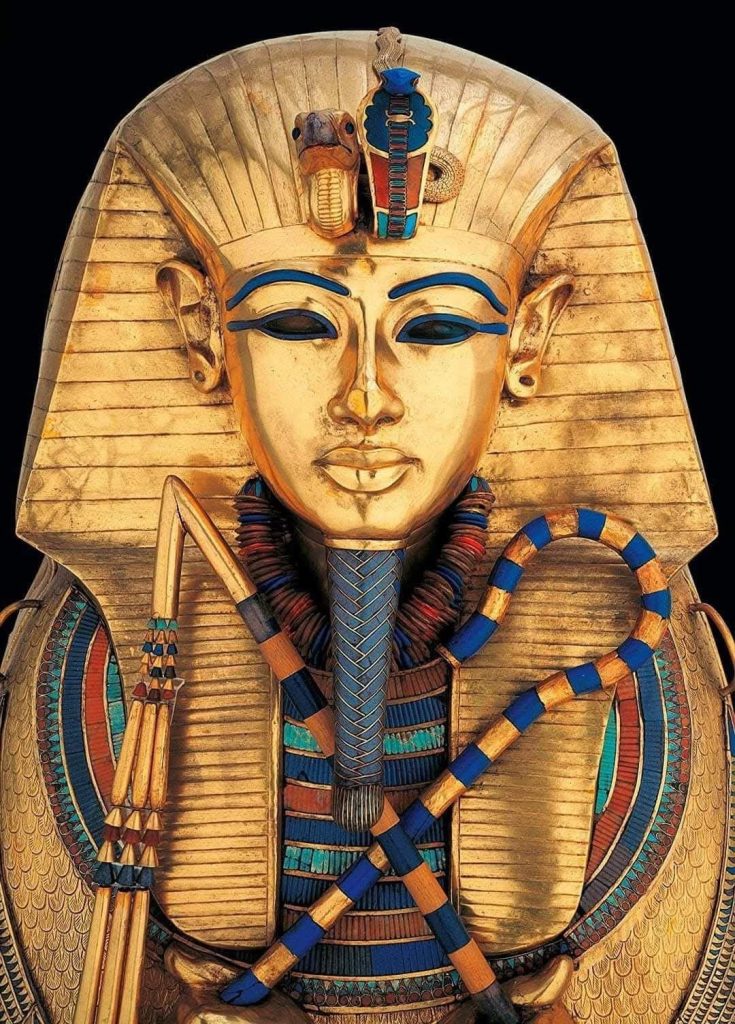

The innermost coffin of Tutankhamun stands as one of the most remarkable artifacts from ancient Egypt, reflecting the artistry, spiritual beliefs, and craftsmanship of the New Kingdom’s 18th Dynasty. Crafted from solid gold and adorned with intricate incised decorations and inscriptions, both on the interior and exterior, the coffin bears the name and epitaph of the young king alongside protective texts intended to guide and safeguard him in the afterlife. Semiprecious stones and colored glass are meticulously inlaid, enhancing its aesthetic and symbolic significance. The coffin itself is shaped in the form of Osiris, the Egyptian god of the afterlife, holding the sacred heka scepter and flail, which represent power and dominion. Protecting the king’s forehead are the vulture and the uraeus, or rearing cobra, symbols of divine authority and protection. Additionally, the divine beard, crafted from gold and inlaid with blue glass, further underscores the pharaoh’s connection to the gods, emphasizing his divine status in the afterlife.

The coffin, often referred to as the solid gold coffin or the innermost shrine, is entirely made of gold and weighs approximately 110.4 kilograms (243 pounds). Within this coffin lay the mummified remains of King Tutankhamun, whose head was adorned with the iconic gold funerary mask that has since become one of the most recognizable symbols of ancient Egypt. This coffin is the third and innermost of a set of three anthropoid coffins designed to nest within one another, a practice intended to provide multiple layers of spiritual and physical protection for the deceased king. The mummy of Tutankhamun now rests in the outermost coffin, which remains within the tomb (KV62) located in the Valley of the Kings on the west bank of Luxor. Following the tomb’s discovery, the inner and middle coffins were transferred to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, while the outer gilded coffin was left inside the burial chamber.

The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in November 1922 by British archaeologist Howard Carter marked a watershed moment in the field of Egyptology. The excavation received extensive international media coverage, captivating the public’s imagination and igniting a fascination with ancient Egypt that endures to this day. The tomb’s burial chamber measures approximately six meters by four meters and houses the outermost rectangular quartzite sarcophagus. At each of its four corners stands a figure of a protective deity with outstretched wings, symbolically guarding both the sarcophagus and the mummy within. Inside the sarcophagus are the three anthropoid coffins, each depicting the king in the traditional Osirian position, with crossed arms holding the symbols of kingship. This arrangement reflects the ancient Egyptians’ belief in the afterlife, where the pharaoh, like Osiris, would be resurrected and granted eternal life.

Howard Carter’s first glimpse of the tomb’s sealed doorway at the bottom of the staircase became an iconic moment in archaeological history. However, the romanticized narrative of discovery often overlooks the complexities and challenges of conducting archaeological work in early 20th-century Egypt, which was then under British colonial rule. Carter’s characterization of the moment as “a thrilling moment for an excavator, quite alone save his native staff of workmen” reflects the colonial mindset of the time, marginalizing the essential contributions of Egyptian laborers who played a vital role in the excavation process. The ease with which Carter dismissed figures such as Ra’is Ahmed and other Egyptian participants underscores the broader context of colonialism that shaped archaeological practices during this period. These historical oversights, while often omitted from popular accounts, are crucial to understanding the social and political dynamics that influenced the excavation and interpretation of Tutankhamun’s tomb.

The craftsmanship of the gold coffin is unparalleled, showcasing the advanced metallurgical skills of ancient Egyptian artisans. Every detail, from the precise incisions of the hieroglyphs to the delicate inlay of stones and glass, reflects the profound cultural and religious significance attributed to the pharaoh’s journey to the afterlife. The coffin’s design was not merely decorative; each element served a symbolic purpose, aligning with the ancient Egyptians’ belief in the necessity of preserving both the physical body and the spiritual essence of the deceased. The protective deities depicted on the coffin, including representations of Isis, Nephthys, Selket, and Neith, were believed to safeguard the king’s soul as he navigated the challenges of the afterlife, ensuring his successful transition to immortality.

The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb provided an unprecedented glimpse into the material culture of ancient Egypt, revealing a wealth of artifacts that illuminated various aspects of daily life, religious practices, and royal customs. The gold coffin, as the final resting place of the young pharaoh, holds particular significance as a symbol of both his royal status and the ancient Egyptians’ complex beliefs regarding death and the afterlife. Its exquisite beauty and craftsmanship have made it one of the most iconic artifacts in the world, admired by millions of visitors to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Beyond its aesthetic appeal, the coffin serves as a tangible link to a civilization that, despite the passage of millennia, continues to captivate the imagination of people worldwide.

Tutankhamun, often referred to as the Golden Pharaoh, reigned during a period of political and religious transition in the New Kingdom. His early death, at approximately 18 or 19 years of age, has long been the subject of speculation, with theories ranging from natural causes to accidents and even foul play. Despite the mystery surrounding his demise, his tomb’s discovery provided a rare and invaluable snapshot of ancient Egyptian funerary practices, as well as insights into the wealth and power of the 18th Dynasty. The treasures found within the tomb, including jewelry, furniture, weapons, and ritual objects, collectively represent one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of the 20th century.

The innermost coffin, with its combination of artistic mastery and spiritual symbolism, epitomizes the ancient Egyptians’ profound reverence for the afterlife. Its solid gold construction not only reflects the wealth and status of the young pharaoh but also embodies the belief that gold, associated with the flesh of the gods, would ensure the king’s eternal life. The protective inscriptions and iconography adorning the coffin were intended to guide Tutankhamun through the perilous journey of the afterlife, ultimately securing his resurrection and immortality. In this sense, the coffin is more than a burial container; it is a testament to a civilization whose spiritual and artistic achievements continue to resonate with humanity’s collective imagination.