Stepping back into the vibrant and complex world of 2nd-century Rome, we encounter one of the most fascinating archaeological discoveries from the ancient empire: the Surgeon’s Villa. Located in the heart of the Roman town of Rimini—ancient Ariminum—this luxurious Roman residence stands not only as a symbol of wealth and refined taste but also as a testament to the medical knowledge and skill of the time. Named after the surgical tools found during excavations, the Surgeon’s Villa paints a vivid picture of life in the Roman Empire and invites us to delve deep into the social, medical, and architectural history that shaped it.

The villa is believed to have belonged to a physician named Eutyches, an Eastern military doctor known for his surgical expertise. This attribution stems primarily from the discovery of an incredibly rare and well-preserved set of surgical instruments found within the ruins of the home. These tools included scalpels, forceps, tweezers, and probes, many of which were made of bronze and iron, and some even bore the names of their intended medical use. The presence of this surgical kit gives us a unique glimpse into Roman medical practices, suggesting a highly developed understanding of surgery and patient care at the time. Eutyches, who likely worked for the Roman army, would have tended to soldiers wounded in battle, and the villa may have doubled as a treatment center for both military and civilian patients.

The layout and structure of the villa reflected the wealth and education of its owner. Featuring multiple rooms adorned with elegant mosaic floors, columned courtyards, and artistic frescoes, the villa embodied the sophistication of Roman residential design. One could imagine Eutyches, after a long day of treating patients, walking through his home’s marble-clad atrium or resting beneath the shade of a pergola in the garden. The architectural elements combined comfort with classical Roman aesthetics, emphasizing symmetry, harmony, and luxury.

However, the fortunes of the Surgeon’s Villa would soon take a dramatic turn. Sometime in the mid-3rd century A.D., a catastrophic fire broke out, devastating the villa and reducing much of it to rubble. The once-lively halls and carefully curated rooms were consumed by flames, leaving behind only charred remains and shattered memories. This destruction marked not just the end of an era for the Surgeon’s Villa but also a turning point in the urban landscape of ancient Rimini.

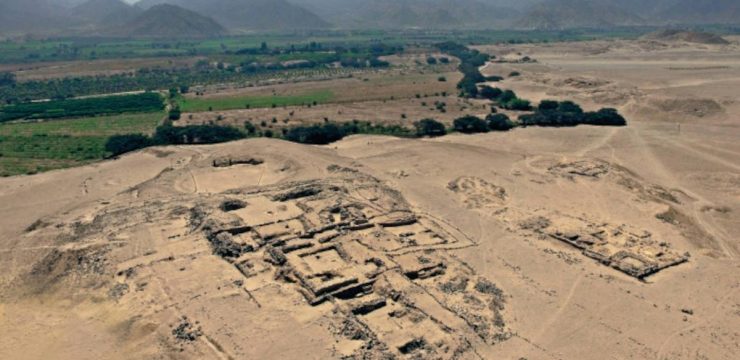

Yet in true Roman fashion, the city’s inhabitants found a way to reclaim and repurpose what remained. Rather than abandoning the site entirely, they used the rubble and remnants of the villa as foundational material for new construction. The ruins were incorporated directly into the city’s fortification walls, built to defend against increasing threats from Germanic tribes and internal strife. In this way, the Surgeon’s Villa became quite literally part of the fabric of Rimini’s evolving infrastructure—its walls became walls of defense, its floors paved the way for future generations.

As the Roman Empire transitioned into Late Antiquity, the site saw yet another transformation. Around the 5th century A.D., a stunning palace complex began to take shape near the ruins of the Surgeon’s Villa. This Late Antique Palace introduced a new level of grandeur to the area, featuring polychrome mosaics with geometric and floral motifs, an apsidal hall designed for public or ceremonial use, and a nymphaeum—a decorative fountain often associated with divine or mythological themes. These luxurious additions signaled a renewed era of wealth and artistic expression, though one marked by shifting religious and political ideologies.

The palace stood as a beacon of opulence and civic pride, its mosaics reflecting the changing aesthetics of the time while still maintaining echoes of classical traditions. Unlike the villa, which served both as a home and workplace for a doctor, the palace was likely a center of elite social gatherings and official functions. This evolution in use also reflects broader societal shifts, as cities like Rimini adapted to the waning influence of Rome and the rise of localized governance and Christianity.

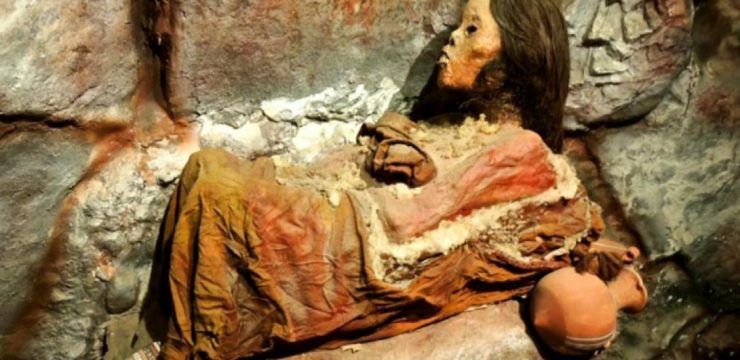

But time is relentless, and like many grand structures of antiquity, the palace too began to crumble. By the 6th century A.D., the site was no longer a place of healing or celebration—it had become a resting ground for the dead. The remnants of once-glorious architecture gave way to a somber new chapter. Archaeological excavations revealed numerous graves scattered across the area, many of them built directly over the ruins of the palace and villa. These tombs, though modest, provide meaningful insights into the lives of those who lived during this transitional period in history.

Some of the burials featured simple grave goods—ceramic jars, small coins, or personal ornaments—offering clues about the identities, beliefs, and economic conditions of the deceased. The shift from a vibrant medical residence to a burial ground underscores the constant evolution of urban spaces in response to changing historical circumstances. Where once stood the elegant columns of a doctor’s home and the dazzling mosaics of a noble palace, now lay the quiet testimonies of individuals who lived through the collapse of an empire and the birth of medieval Europe.

Today, the Surgeon’s Villa stands as more than just a ruin—it is a historical mosaic of Roman civilization itself. It tells a story of innovation and resilience, of loss and rebirth, of how one location can bear witness to so many facets of human existence across centuries. From the delicate touch of a physician’s hand to the determined labor of city builders and the silent dignity of those buried long ago, the villa continues to speak to us through stone, artifact, and imagination. For archaeologists, historians, and curious minds alike, it remains a site of wonder and revelation, inviting us to explore not only the past but also the enduring human spirit that connects us to it.