Certainly! Here’s a rewritten version of your 879-word article in fluent American English, keeping the original meaning fully intact and ensuring a seamless flow throughout, without section dividers or subheadings:

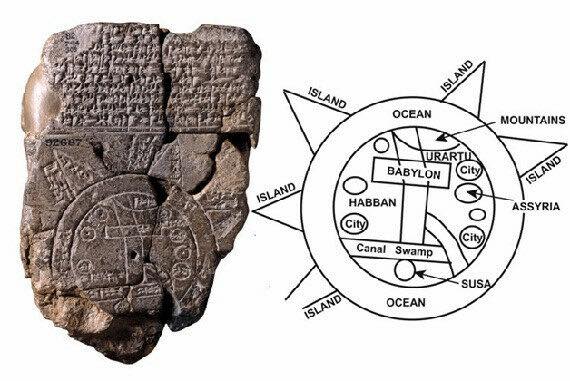

The Imago Mundi, a Babylonian clay tablet known as the oldest world map ever discovered, offers a fascinating glimpse into how ancient people understood their place in the universe. Dating back to the 5th century BC, this extraordinary artifact doesn’t just represent land and water—it reflects the ancient Babylonians’ attempt to chart both the physical world and the cosmos through their own cultural and spiritual lens. Its importance lies not only in its antiquity but also in the unique insight it gives us into the early human effort to make sense of the world using limited tools and vast imagination.

This ancient map was discovered in the ruins of Sippar, a once-flourishing city situated along the eastern banks of the Euphrates River in what is now southern Iraq. Located north of the famed city of Babylon, Sippar was an important center for scholarship and worship. When archaeologists unearthed the clay tablet, they realized that they were not merely holding a depiction of geography, but a cultural treasure that captured the Babylonian vision of how the world functioned both on earth and in the heavens.

At the heart of the map lies Babylon, positioned firmly in the center, symbolizing the city’s perceived importance to the people who created it. This choice wasn’t unique to Babylonian society; many ancient civilizations placed their own major cities—such as Jerusalem or Athens—at the center of their maps, reflecting the natural human tendency to see one’s homeland as the core of existence. For the Babylonians, who had no access to modern geography, digital maps, or global navigation systems, this central position for Babylon wasn’t just symbolic; it was practical. From their point of view, life radiated outward from Babylon, which served as the economic, spiritual, and political center of their world.

The map itself is circular in form and features two prominent bodies of water. These are believed to represent the bodies of water that were crucial to the survival of the Babylonian civilization. The map also includes seven small circles that surround the central landmass, which likely symbolize distant cities or mythical islands. These peripheral locations, along with the waters surrounding them, are labeled in cuneiform script. The inscriptions describe a “salt sea” and a “river of bitter water,” perhaps reflecting the boundaries of their known world, or representing symbolic barriers between the known and the unknown.

Beyond these details, the tablet contains references to notable ancient locations, including Assyria, Elam, Urartu, Der, Bit Yakin, and Habban, among others. Some cities are named directly, while others remain anonymous, hinting at forgotten settlements or possibly mythical lands. A curved line likely represents the Zagros Mountains, a prominent natural landmark in the region, while parallel lines beneath the depiction of Babylon might illustrate the marshy southern landscape of modern-day Iraq. This artistic portrayal, though not geographically precise by today’s standards, is a surprisingly thoughtful attempt to depict both topographical and spiritual boundaries using the knowledge available at the time.

What makes the Imago Mundi even more remarkable is that the inscriptions suggest it is a copy of an older, now-lost map. This means the tradition of mapping and organizing the world may stretch even further back in Mesopotamian history than this tablet alone can reveal. Though imperfect and limited by its era, this clay tablet captures the extraordinary effort of early astronomers and geographers to understand their world in ways that merge physical reality with spiritual and mythical concepts.

Rather than a strictly literal map, many scholars interpret the outer regions of the map as mythological representations. The seven surrounding “islands” could signify gates or realms that bridge the gap between the earthly plane and the divine. These were not just places one could travel to—they were thought to exist at the intersection of the real and the legendary, perhaps representing regions of the heavens or thresholds between the mortal and immortal. The concept of merging terrestrial and celestial realms wasn’t unusual for the Babylonians, who were deeply invested in astronomy and divination. Their understanding of the heavens was intertwined with their religious beliefs, and maps like this may have served as both practical and symbolic tools for navigating the mysteries of the universe.

The reverse side of the Imago Mundi offers even more depth. It features constellations that align closely with today’s zodiac signs, demonstrating the Babylonians’ advanced knowledge of the stars and their patterns. By incorporating these astronomical symbols, the map becomes more than just a depiction of geography—it transforms into a cosmological chart, reflecting a culture that viewed the earth and sky as part of a unified system. Every mountain, city, and body of water had its place in a grand cosmic order, and this tablet is a testament to that vision.

In many ways, the Imago Mundi serves as a historical mirror, reflecting the Babylonians’ attempt to understand and explain their reality. With clay and a stylus, they shaped a worldview that integrated observation, belief, and imagination. Though we now possess satellites, GPS, and detailed global maps, the impulse behind this ancient artifact remains familiar—the need to define our place in the universe. Through their creative and intellectual efforts, the Babylonians laid the groundwork for future explorations in cartography, astronomy, and philosophy.

Today, the Imago Mundi stands not just as the oldest known map, but as a symbol of early human curiosity and our enduring quest to comprehend the world around us. It reminds us that long before we had the technology to map continents or chart galaxies, we had the vision to dream and the wisdom to record those dreams in clay. This simple yet profound artifact continues to inspire modern scholars, showing how even the earliest civilizations sought to bridge the distance between the known and the mysterious through knowledge, art, and belief.