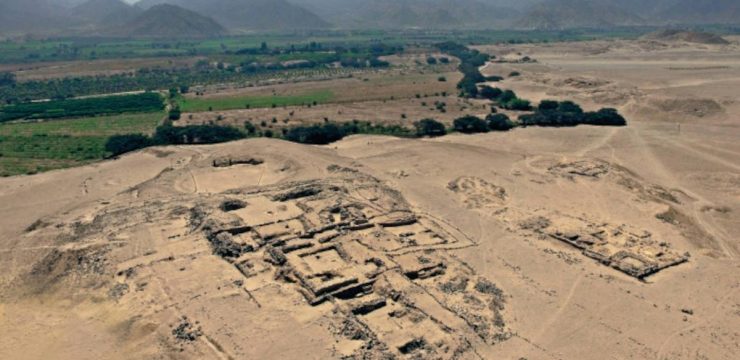

During the 1970s, a groundbreaking discovery was made near the modern-day city of Varna, Bulgaria. Archaeologists working in the area uncovered an expansive burial site dating back to the 5th millennium BC. What they had unearthed was a vast Copper Age necropolis—an ancient cemetery—containing what are now recognized as the oldest known golden artifacts in the world. Although the entire site proved to be of tremendous historical and archaeological importance, one particular burial stood out above the rest: Grave 43.

Grave 43 was unlike anything previously discovered from that era. Within this grave lay the remains of a high-status male who had been buried with an astonishing array of treasures. The man, now referred to as the Varna Man, was not only buried with gold items, but also with symbols of power and authority, such as a gold scepter and even a solid gold sheath covering his genitals. These luxurious grave goods suggested that he held a dominant position in his society—possibly a tribal leader, chieftain, or spiritual figure of great influence. His burial marked the earliest known example of a male elite interment in European history, and the opulence of his tomb has since become a defining symbol of the ancient Varna culture.

The Varna culture itself began to emerge over 7,000 years ago along the shores of the Black Sea. This early European society was far more sophisticated than once believed, demonstrating a level of technological, artistic, and social development that surprised researchers. One of its most remarkable achievements was the production of gold artifacts, making the Varna culture the first known civilization to master goldsmithing. These advances predated similar developments in both Mesopotamian and Egyptian societies, placing Varna at the forefront of early human innovation.

Between roughly 4600 and 4200 BC, the people of Varna began working extensively with copper and gold, developing methods of smelting and shaping these metals with extraordinary skill. This marked the beginning of organized metallurgy in Europe. As their metallurgical techniques improved, so did their ability to engage in trade. The Varna culture established connections with surrounding communities and distant regions, facilitating the exchange of materials, ideas, and cultural practices. Over time, Varna evolved into a thriving commercial hub that linked the Black Sea to the wider Mediterranean world. These trade routes were crucial in the diffusion of both goods and cultural influences, elevating Varna’s status as a central point of contact and exchange in prehistoric Europe.

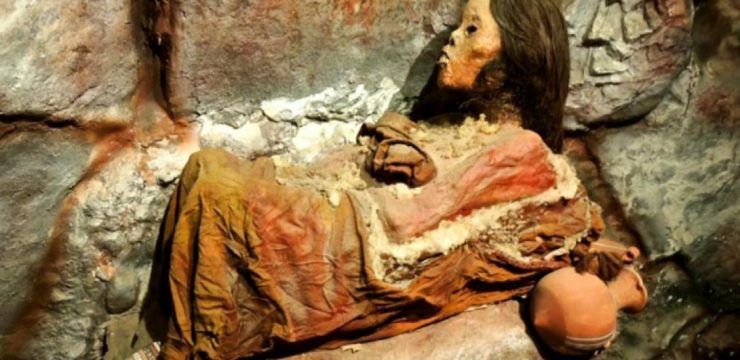

The archaeological site at Varna provided a wealth of insight into the social structure of this ancient society. Excavations revealed stark differences in the ways people were buried, shedding light on a community that was clearly divided by status and wealth. Members of the elite were interred in elaborate graves filled with gold jewelry, tools, and symbolic items, while others were buried with far fewer possessions, indicating a lower rank in the social hierarchy. The presence of grave goods in such quantity and variety suggested a society that had already developed complex rituals surrounding death and the afterlife.

Researchers were particularly intrigued by some of the more mysterious aspects of Varna’s burial traditions. Not all graves contained human remains. Several of them, labeled as symbolic burials or cenotaphs, held no skeletons at all but were nonetheless filled with expensive and meaningful objects. Some of these graves included clay masks or figurines, while others featured amulets commonly associated with female figures, perhaps representing fertility or divine protection. These findings suggest that funerary rites may have involved ceremonial practices or symbolic representations of individuals who could not be physically buried—perhaps due to their deaths occurring far from the community or under special circumstances. These traditions point to a rich spiritual or religious life that emphasized remembrance, ritual, and symbolism.

Despite its eventual decline toward the end of the 5th millennium BC, the Varna culture left a lasting impact on the development of European civilizations. Its pioneering work in metallurgy laid the technical foundation for future societies that would build upon and expand their knowledge. The Varna people not only demonstrated an exceptional command of metalworking but also developed social systems that emphasized centralized leadership, wealth differentiation, and ceremonial grandeur. These aspects of Varna society likely influenced the rise of similar structures in other parts of Europe, where hierarchical governance and symbolic burial became more widespread over time.

Moreover, the Varna culture’s advancements in trade and craftsmanship contributed to the broader exchange networks that would later support the growth of Bronze Age societies. Their artifacts, especially those crafted in gold, are not only artistic masterpieces but also historical documents that reveal the values, skills, and complexity of early European communities. Their centralized approach to governance, combined with deep social stratification and a strong focus on ritual practices, set a precedent that resonated throughout the continent in centuries to come.

What makes the story of Varna so compelling is not just the sheer antiquity of the gold artifacts or the grandeur of the burial sites, but the way these findings challenge previously held assumptions about the capabilities of prehistoric societies. Prior to these discoveries, many scholars believed that early European communities were relatively simple and unsophisticated. The Varna necropolis shattered those assumptions, offering concrete evidence of a civilization that was rich, organized, and highly innovative. In doing so, it redefined the narrative of early European development and underscored the importance of the region in the broader story of human civilization.

Today, the legacy of the Varna culture continues to inspire scholars and history enthusiasts alike. Its contributions to metallurgy, trade, and social organization remain subjects of active study, and its influence can be seen in the cultural DNA of Europe. The Varna necropolis stands not only as a burial site, but as a testament to the ingenuity and vision of a people who forged a golden age long before recorded history began.